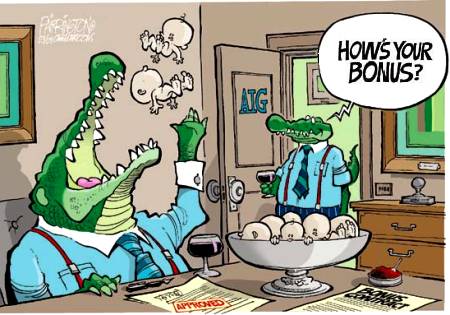

Whatever is to be done about that whole AIG thing?

Great minds often think alike. Not necessarily in lockstep, but sometimes two different (and equally excellent) people come to the same conclusion. Take, for example, one of my long-time journalistic heroes, Joe Conason:

The popular urge to claw back the bogus bonuses paid by American International Group is irresistible and fully justified, but should the Treasury someday retrieve every single bonus dollar, that total of $165 million will make no difference to anyone except a few disgruntled traders. From the jaded perspective of the financiers, the uproar over the AIG bonuses may provide a welcome distraction from far more important (and lucrative) abuses in the world's offshore tax havens.[...]

According to the Government Accountability Office, nearly all of America's top 100 corporations maintain subsidiaries in countries identified as tax havens. As the GAO notes, there could be reasons other than avoiding the IRS to set up branches in places such as Singapore, Luxembourg and Switzerland, where taxes are light or nonexistent and keeping clients' illicit secrets is considered a matter of national pride.

But what reason other than evasion could there be for Goldman Sachs Group to set up three subsidiaries in Bermuda, five in Mauritius, and 15 in the Cayman Islands? Why did Countrywide Financial need two subsidiaries in Guernsey? Why did Wachovia need 18 subsidiaries in Bermuda, three in the British Virgin Islands, and 16 in the Caymans? Why did Lehman Brothers need 31 subsidiaries in the Caymans? What do Bank of America's 59 subsidiaries in the Caymans actually do? Why does Citigroup need 427 separate subsidiaries in tax havens, including 12 in the Channel Islands, 21 in Jersey, 91 in Luxembourg, 19 in Bermuda and 90 in the Caymans? What exactly is going on at Morgan Stanley's 19 subs in Jersey, 29 subs in Luxembourg, 14 subs in the Marshall Islands, and its amazing 158 subs in the Caymans? And speaking of AIG, why does it have 18 subs in tax-haven countries? (Don't expect to find out from Fox News Channel or the New York Post, because News Corp. has its own constellation of strange subsidiaries, including 33 in the Caymans alone.)

When the cost of these shenanigans was last estimated two years ago, the U.S. government's annual loss in revenue due to tax avoidance by major corporations and super-rich individuals was pegged at about $100 billion -- considerably more than a rounding error, even today. But of course that is only a rough assessment, as is the estimate of $12 trillion in untaxed assets hidden around the world. Nobody will know for certain until the books are opened and transparency is established.

Now take another--Linda McQuaig:

Don't get me wrong: I'm not against tarring and feathering those AIG guys who helped destroy the world economy with their financial manoeuvres, and then received million-dollar bonuses to undo their own handiwork.But focusing just on them is like just going after the crude thugs who unleashed dogs on Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib, without noticing that their actions were the product of a climate of lawlessness and vengeance fostered by the White House.

Similarly, for several decades now, the financial and corporate elite has championed an unbridled capitalism, and pressed for the removal of crucial regulations needed to protect the public. It has also championed an ethos of greed that justified extraordinary compensation, and very low tax burdens, for those at the top.

In this climate -- with regulations stripped away, an intense fanning of the flames of acquisitiveness and the prospect of ever-larger bonuses dangled in front of them -- are we surprised that some Wall Street types unleashed their inner dog in ways that took little account of the public interest?

...and that took a beeline for all those offshore banks where transparency is a dirty word?

Offshore banks and other tax shelters should finally be called by their right name: ACCOMPLICES.

Last time I looked, aiding and abetting a crime was a crime unto itself, and an accomplice is held guilty right along with the main perpetrator. The laws of many a land all agree on this point. They wouldn't let a band of gangsters on a ghetto street get away with murder--so why allow it in the financial district?

The answer, I suspect, is because the banksters know how to bury a body where it won't be easily found. And where better than in a convoluted, opaque foreign banking system? Especially when the country where the accomplice-bank is located plumes itself on its "discretion" and "safety"?

Of course, those countries where the accomplice-banks squat are invariably small. Small geography, small population, small resources, small tax base. They don't produce much because they don't have much to produce with. And so it leads to a certain smallness of mind, as well. Particularly when it comes to cash. After all, if you ain't got money comin' in from anyplace else, shoot, why not take it from a well-heeled overseas crook? Especially if that crook dresses in Armani, Zegna, and every other trendy international name in the lexicon? Such things lend an awful lot of glitter and panache to a place that's home to just three inbred farmers and one cross-eyed cow*...

So of course it should come as no surprise that the infamous Stanford Bank would have its centre of thievery highway robbery offshore banking in Antigua, an island with a population of no more than maybe 100,000 souls.** And of these, how many pay taxes? How many make enough that anyone would levy taxes on them? And if collected, what good would that piffling amount of tax income do? The parliamentarians would all have to take second jobs at that rate. And how many jobs are on that island to begin with?

Obviously, political alternatives (such as communal rule, for example) aren't being considered. So it's little wonder that the local politicos, despite their insistences to the contrary, don't run a very tight ship where banking and transparency are concerned. And as long as that money keeps flowing, nobody worries much.

Until it all jumps up to bite them in the ass. Which, as bad luck would have it, is now the case. Allen Stanford was running an elaborate Ponzi scheme--who knew?

Well, the Antiguan authorities should have known--had they been keeping track. Which they weren't. After all, their little island nation had a reputation to uphold. And that reputation was not for transparency and integrity; it was for "discretion". Integrity and transparency don't pay the bills, much less build glitzy tourist attractions for all those foreign sun-seekers! What does? Cold, hard, foreign cash.

And, as the old Roman saying has it, Pecunia non olet. Money has no odor. Even if the way it was gotten stinks to high heaven, somehow that cash always manages to smell sweet...***

But let's not bog down in the question of whether money smells. I can tell you what stinks to the highest heaven, and so can my fellow Canadian:

Greed had become the new black. No one even seemed embarrassed to show it. As Barbara Amiel once said, "I have an extravagance that knows no bounds." This wasn't something she cooed privately into the ear of her husband, but rather boasted publicly to fashion magazine Vogue.Of course, any attempt to critique greed or the unbridled capitalism that accommodates it is quickly dismissed. Resistance is pointless, we're told. Greed is simply natural -- as basic to the human condition as jealousy, anger, pride, pimples.

Linda McQuaig nailed it. The root of the problem lies not with any individual corporation, or any single small country specializing in offshore banking. The problem is greed, and more specifically, the way greed has been entrenched in our cultures and enshrined in our laws. Gordon Gekko's downfall in Wall Street should be proof enough that the man is wrong about the nature of the beast: Greed is not good. Greed kills. Greed wrecks entire economies, and not just in small countries; big ones are just as vulnerable. In fact, the bigger and more interconnected and globalized the economy, the more the old saying holds true: The harder they fall.

Unfortunately, it seems that a lot of real-life Wall Streeters never watched that movie to the end. They don't read good books, either. And they sure don't read what Joe Conason has written...

Whatever the accurate accounting proves to be, it is certain to exceed hundreds of billions annually worldwide. That is money every country will need badly for years, to repay debt, finance reconstruction, and fund services, as the world economy struggles to revive itself. Even in the developing countries, where incomes are much lower and billionaires tend to be scarce, the annual revenue loss could be as much as $50 billion -- enough to meet the U.N.'s Millennium Development Goals (if only the money were not stolen by local elites and wired away to numbered accounts in tax havens).None of these tax havens could exist without the connivance or at least the cooperation of the world's most powerful governments, which remain dominated by financial industry lobbyists even now.

It sure looks hopeless at the rate things are currently going, does it not?

But wait...Linda McQuaig hasn't just nailed the problem of shrugging one's shoulders at greed, she has also unearthed some pretty earth-shaking stuff about who the real Atlases are that hold this world aloft:

[T]he late economic historian Karl Polanyi noted that resisting the rapacious effects of the unregulated market is also natural, perhaps even more basic in humans.Polanyi pointed out that the rise of capitalism centuries ago was so disruptive to the lives of ordinary people -- who were forced into mines and factories after losing their rights to the common fields -- that it produced a counter-reaction aimed at controlling the market.

Indeed, Polanyi argued that while capitalism was a carefully planned set of laws designed by the financial elite, the reaction to capitalism -- protests, unionization, political agitation -- was a natural set of responses that emerged spontaneously from the masses.

The impulse to resist unbridled capitalism -- with its resulting extreme inequality and economic domination by the rich -- is basic and has persisted throughout the centuries, according to Polanyi.

It culminated in the rise of the social welfare state in the early decades after World War II -- an era in which the market excesses of the 1920s were reined in by financial regulation, and tax and spending policies led to greater social equity. In both the U.S. and Canada, there was real growth in the incomes of the middle and lower classes.

And you'll note that all that was done without telling the common people to invest, much less in offshore banking.

Free-marketers are always telling small countries to take harsh medicine (poison, really) to "cure" what ails them financially. This socialist scribbler would give the same advice, but a different kind of medicine. Mine would kill only the crooks (big ones especially) and cure the economy.

Ready for a dose?