Legendary Zapatista Leader Comandanta Ramona Has Died She Struggled with Cancer for Ten Years; "Other Campaign" Temporarily Suspended for Her Funeral

By Andrew Kennis

Special to The Narco News Bulletin

January 7, 2006

TONALÁ AND SAN CRISTÓBAL DE LAS CASAS, CHIAPAS, MÉXICO: After a decade-long bout with cancer of the kidney, Zapatista leader Comandanta Ramona died early yesterday morning. Choking back tears and with a wavering voice, Subcomandante Marcos made the public announcement of Ramona's death in the midst of the Chiapas segment of the nationwide six month Zapatista led "Other Campaign."

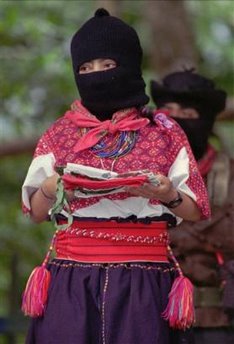

Comandanta Ramona, 1959-2006

“I want everybody to listen to what I am about to say without any interruptions. Comandanta Ramona died yesterday… The world has lost one of those women it requires. Mexico has lost one of the combative women it needs and we, we have lost a piece of our heart,” said Marcos. The self-nicknamed “Delegate Zero” went on to say that the activities planned for the next few days would be cancelled and that the Other Campaign delegation would be immediately travel to Oventic for funeral activities that were closed to the public. The emotional announcement came around 4pm central time yesterday, after an abrupt hour-long pause to a nearly six-hour long town-hall like meeting in the small coastal town of Tonalá.

An advocate for women’s rights and artisanship, Ramona woke up yesterday feeling weak, but still traveled from Oventic to San Cristóbal de las Casas. During the course of the trip, she passed away.

The last public appearance by Comandanta Ramona came this past September, when she spoke in front of the plenary sessions that were held to plan the Other Campaign deep in the Lacandon Jungle, in the heart of Zapatista territory.

Ramona was the first member of the Clandestine Indigenous Revolutionary Committee (CGRI), the leadership body of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), to have died since the end of their uprising twelve years ago. Her struggle with cancer was a long one, in which she received a kidney transplant in 1996 after extensive grassroots fundraising. Most sympathizers consider the transplant as having brought her an extra decade of life. As a result of her illness, Ramona made few public appearances since the Zapatistas came into the public eye following their uprising, but she nonetheless made her mark in a number of ways within the influential indigenous rebel group and far beyond, with its supporters.

In 1993, Comandanta Ramona, together with Major Ana María, extensively consulted indigenous Zapatista communities (back then, still underground and not public) about the exploitation of women and subsequently penned the Revolutionary Laws of Women. On March 8 of that year, the Revolutionary Laws were passed (in English, and in Spanish).

Ramona was a petite, soft-spoken woman charged with significant responsibilities, such as having been entrusted with the military leadership in San Cristóbal during the uprising in 1994. In February of that year and after the Zapatistas called a cease-fire to the twelve-day long uprising in response to mass peace marches, Ramona was the first Zapatista representative to speak during peace talks with the government. Two years later, when the Mexican authorities forbade the Zapatistas from participating in the National Indigenous Congress in Mexico City, the frail and ill-struck Ramona was asked to represent the Zapatistas. The plan worked as the government conceded to Ramona and she went on to represent the Zapatistas, speaking in front of 100,000 supporters in Mexico City’s Zocalo during the important nation-wide indigenous gathering.

The Mexican government, baffled by the popularity of a poor indigenous woman, made numerous attempts to undermine her influence. In 1997, it went so far as to state that the rebel leader had died and when she made public appearances that proved otherwise, authorities accused the Zapatistas of having used a "double."

Ramona's death is reflective of a health care crisis that the impoverished indigenous communities of Chiapas continue to suffer from. In the highlands of the southeastern Mexican state, where most of Chiapas’ indigenous residents live, there are no hospitals. The state government has promised for years to build a hospital in San Andrés Larráinzar (the same town that peace accords between the Zapatistas and the Mexican federal government were signed in 1996 but never implemented). However, the promise to build such a hospital has not been acted upon and Chiapas continues to lack crucial health care resources in its remote regions. Only in San Cristóbal, which is anywhere between two and twelve hours away from most indigenous communities, can women access preventative studies that could save the lives of women with early detections of cancer. In addition to the lack of hospitals, medical costs are often prohibitive to many of Chiapas’s poor and infirm.